Roof-top nesting gulls within the Birmingham boundary

Roof-top nesting gulls within the Birmingham boundary

|

Between 2008 and 2011, Jim Winsper conducted a study of roof-top nesting gulls within the boundary of the City of Birmingham (see Figure 1). Lesser Black-backed Gull is the principal species involved with a much smaller number of Herring Gulls. The findings of the study are presented below.

Jim Winsper

Jim Winsper

Prior to the mid 1950s, Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus and Herring Gull Larus argentatus were regarded as very scarce passage migrants or rare visitors to this region (Harrison & Harrison 2005). During the period mid 1950s through to 1986 the regional status of both gulls changed. They were now associated as being resident birds of winter months with large roosts becoming established at major reservoirs; at the same time they were also being recognised as becoming increasingly more numerous on passage. Both species are still to be found in large numbers during the winter period, scavenging at land fill sites, feeding and loafing on farmland and recreation areas and continuing to roost at the region's larger water expanses. As from 1986 the regional status of Lesser Black- backed Gull changed once again, now being regarded as an increasingly numerous breeding species (WMBC Checklist Emley 2011). Since 1999 the same breeding status also applies to Herring Gull, albeit in much smaller numbers than Lesser Black-backed Gull. The recent regional history of both species of gull is thoroughly documented in the West Midland Bird Club publication "The New Birds of the West Midlands" (Harrison & Harrison 2005).

Today, the sight of Lesser Black-backed Gulls and to a lesser extent Herring Gulls, wheeling above their rooftop breeding colonies during spring and summer months is commonplace in many areas within our region and especially so within the Birmingham boundary. My fascination with this relatively new phenomenon was initially fuelled in 1987 when, along with two colleagues, we came upon a roof-top nest located close to Birmingham city centre that contained two downy Lesser Black-backed Gull chicks. This proof of breeding is the first record to be documented at this location for this species. Prior to this in 1986, the breeding of Lesser Black-backed Gulls (two pairs) was proven in Worcester and this record is a regional first and the commencement of the bird's current status category.

While my study may well be the first of its kind for this exact location, the study of urban roof-top nesting gulls is not new. Peter Rock has an on-going survey that covers the West Country, South Wales, Gloucestershire and parts of the midlands. This work monitors gull populations and studies their behaviour and the affect that this has on an urban environment. Findings from this study area, referred to as "The Severn Estuary Region" reveal connections with breeding gulls here in the Midlands.

A colour ringing programme is integral within this study and this in itself has provided evidence of a movement of birds between the West Country and this region. This is further supported by Harrison & Harrison (2005) who mention that colour ringed birds that originate from Bristol have been observed summering here in the midlands. These facts combine to indicate that the colonisation of the midlands by Lesser Black-backed and Herring Gulls as breeding birds is, in part, the result of an expansion to their breeding range that has seen them spread in a north-easterly direction from the West Country. This would certainly involve birds from the colonies in Bristol and perhaps Cardiff in South Wales. Both species have extended their breeding range by moving north-east through the Severn Estuary, colonising Gloucestershire and on from there into Worcestershire and elsewhere in the midlands to include this study area.

The trend toward urban breeding by these gulls has continued to gather momentum over the last half century and the following statistics reveal the continued national population increase. From these facts we can gather an understanding of the accelerated growth here in the midlands and place it in context with the national scene.

Somewhat surprisingly, the first reported roof-top nesting by Herring Gull is as recent as 1910 in Port Isaac, Cornwall (Brown & Grice 2005). Within a 100 year period from this report, the estimated total of roof-top nesting Herring Gulls in England has since risen to over 12,000 pairs (Seabird 2000 Mitchell et al 2004). It is, however, Lesser Black-backed Gull that has made the greatest inroads into the midland region. During the 1960s it was reported that an increasingly large number of Lesser Black-backed Gulls had nested on the roofs of buildings in coastal towns and findings revealed a total of eight pairs in two coastal locations in 1969 (Cramp 1971). By 1994 at least 958 pairs had been recorded in 38 towns (Raven and Coulson 1997). Further results from Seabird 2000 (Mitchell et al 2004) show figures of 6550 pairs in 69 colonies in both coastal and inland towns. The growth rate of urban nesting gulls continued at a rate of 17% per annum through the period 1976-1994 (Brown & Grice 2005). Most recently, based on results from the Severn Estuary Region over the period 1994-2004 it is estimated that increases on the current scale would see the national population of urban nesting gulls exceed one million pairs by 2014 (Rock 2005). These remarkable statistics reveal that the steady growth in the ever increasing population of urban nesting gulls shows every sign that it is set to continue.

Since the first record in 1987 in Birmingham, the sustained increase in the number of breeding gulls is an occurrence that has been evident for all to see. Summer time shoppers in Birmingham city centre are constantly accompanied by a cacophony of yelping gulls, a sound that was previously only associated with summer holidays and UK seaside resorts. The aim of this study is to establish the number of breeding pairs of gulls that form this population. In achieving this we can then place a value on any meaningful changes that occur against the figures that are presented at the completion of this four year study that spans the breeding seasons commencing in the spring of 2008 and concluding at the end of August 2011.

The recording area

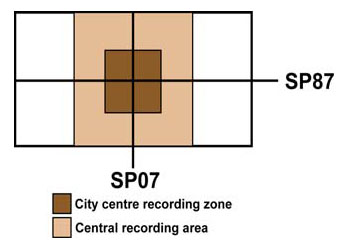

Figure 1 sets out the Birmingham boundary with random locations placed approximately for orientation purposes only.

Figure 1. The recording area

My reasons for choosing this location are based simply on the fact that there is clearly an increasing population of breeding gulls in this area and the boundary itself forms a natural perimeter to work within. At the same time, the area has an extent that is ample enough for one person to cover.

The horizontal and vertical dissecting lines on this map give an Ordnance Survey (OS) grid reference reading for Birmingham city centre as SP070870. While this city centre reference may not fall directly in line with popular opinion as being the accepted central position, it has allowed me to form a 1×1km city centre recording zone that is incorporated within the British National Grid. Some local historians may well prefer the central position for Birmingham city centre as being in Victoria Square and I am not opposed to this. However, it would appear appropriate, given such circumstances, to move this location some 350 metres in an eastward direction to the southern boundary of St. Philips Cathedral Square and in doing so create a dedicated recording zone that is defined by an OS grid intersection. The city centre 1×1km recording zone is therefore defined here as having its centre as St Philips Cathedral Square with its geographical boundaries as:

North: - St Chad's Queensway immediately east of St Chad's Circus.

South: - Junction of Hinckley Street and Theatre Approach.

East: - Junction of Moor Street Queensway and Albert Street.

West: - Junction of Paradise Circus and Great Charles Street.

Figure 2 shows how the 1×1km city centre nest recording zone is placed within the British National OS 1×1km grid. Since the recording of breeding gulls first began in Birmingham in 1987 there has been an uninterrupted reference to a city centre location. This annual practice must then dictate that this is an area of considerable historic importance and that we should endeavour to keep it in place as a recognisable feature with an exact position. From hereon all such records can be related to this zone.

Figure 2.

All of those nests that are located within the 1×1km squares that immediately surround the city centre zone, as shown in figure 2, will from hereon be referred to as the central recording area.

Outside this city centre zone and the central location, colonies are scattered throughout the area in a variety of environments and building types. These sites range from light to heavy industrial factory premises that may be located in high or low density industrial areas, office apartments and retail and commercial business parks. Largely, and perhaps understandably, housing estates are not in common use as nest sites yet. The reason for this is that domestic dwellings in their standard forms of terraced, semi or detached properties are not the preferred choice while there are still plenty of suitable industrial premises that remain unused. There are, however, constructions that are positioned within housing estates, such as shopping centres, public service buildings and the like that are suitable to their requirements. In these instances such buildings may be used or there have been attempts to use them. Clearly these birds, particularly Lesser Black-backed Gull are not put off from their preferred nest location by man and man's daily activities. The potential for both species of gull to increase their regional population and in doing so extend their breeding range in the area, is great. Having said this, there are a variety of reasons that may well thwart any expansion, none more so than the concern of building owners to large colonies of gulls nesting on their roof-tops. The entire population of breeding gulls in any city centre, urban or suburban environment is, to say the least, volatile.

The construction and type of buildings that are used for nest sites vary considerably. These range from low level single storey, through to high rise multi-storey buildings. However, the height of the building does not dictate their choice; it is the design of the roof that initially attracts the birds with flat or shallow pitched roofs being their preference. Low level to mid height buildings with a large expanse of shallow pitched roof construction that incorporate a series of valleys, hold some of the largest colonies.

Timing of the study

The period chosen for the fieldwork, the breeding seasons 2008 through to 2011 inclusive, was designed to run alongside the new BTO atlas fieldwork 2007-2011 (BTO combined breeding and winter atlas). This allowed me to place all gull breeding records into atlas data as well as at region and county level.

Recording methods

The aim of this study is uncomplicated. It is to provide a population figure that comprises of confirmed breeding pairs of roof-top nesting gulls from within this area. The criteria used to establish breeding status is that in current use by the British Trust for Ornithology in order to determine: non-breeding, possible breeder, probable breeding and confirmed breeding. This is a standard method used for all BTO breeding bird survey work.

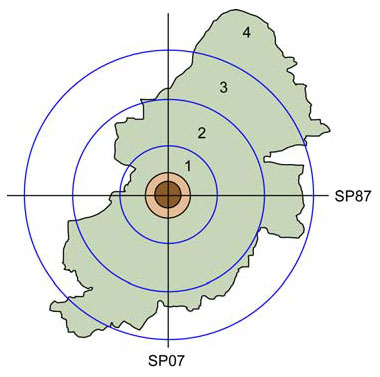

My method to ensure that the area had adequate coverage was to divide it into a series of recording zones. These circular zones, four in all, emanate from the city centre zone. Achieving full coverage of each zone in each of the four years of the survey would go a long way to ensure that all colonies, or at least an extremely high percentage of all colonies, would be detected. As expected, the zones that form the city centre, central area and the inner two of the four, held the highest density of birds. This equates to the fact that these areas contain the most suitable habitat. The perimeter zone, zone four, held the fewest. See figure 3.

Figure 3. Fieldwork recording zones. Zone 1 includes city centre and central area.

Clearly those zones with the fewest birds were less demanding in terms of time spent in that particular area once all of the colonies had been located. As a result of this more time could be devoted to those areas that were densely populated. This assisted in my further effort to attain accuracy, in so much that part of my fieldwork strategy was to monitor the stability of each colony year on year. Across the entire survey area all colonies remained reasonably stable (without meaningful change) throughout the fieldwork period. A full collapse or even part failure in any of the larger colonies would obviously have a major effect upon the final results. When carrying out this annual check, colonies were prioritised in order of size.

Satellite mapping technology and GPS positioning simplified the task of route planning and plotting of the area. Another very useful aid, as a fieldwork companion while searching the area, is the De Luxe large format version of the Birmingham A-Z street guide. This atlas and most of the computerised mapping devices clearly depict the exact habitat, enabling me to identify and seek out those industrial and commercial areas that are the gulls' preferred breeding sites. Once the zones had been thoroughly covered and the colonies plotted it was then a case of criss-crossing the area from site to site in order to establish the number of breeding pairs in each colony.

Results

The results from this study form only part of the midland urban nesting gull scene. Other midland cities, towns and suitable areas also hold colonies; some of which border the Birmingham boundary, sites in West Bromwich and Solihull being examples. Immediately to the west and north-west of this study area lies a swathe of suitable breeding habitat that extends from Cannock in the north-west, through the Black Country to Wolverhampton in the west. To the south-west there are regular records of summering gulls from Worcester city centre and elsewhere in that county.

Having previously stated that my sole aim of this study is to provide numbers that form a benchmark for future studies, it would be impossible to carry out such a task without benefiting your knowledge of the species involved. In doing so, I am convinced that one feature of the pre-breeding behaviour of Lesser Black-backed Gull is worthy of mention should anyone wish to follow up this type of study. My findings relate to a particular detail that could have a bearing upon the accuracy of any final assessment of breeding pairs.

| Behavioural Study - While some breeding sites can be used during the winter period as a roost, birds can begin to gather at their chosen breeding location early in the year, sometimes as early as late January when weather conditions appear right. From this point onward as the true season approaches, courtship activity increases. Such activity can involve a melee of birds, particularly at the larger sites, jostling for position, courtship display and chasing off rivals. All of the birds involved appear to be in full adult plumage, fourth year birds at least. It would be easy to assume that this gathering would eventually form the bulk of the colony population but this assumption may well be incorrect. There is clearly a hierarchy of birds within these groups, birds that are in excess of four years old and are experienced breeders. Other birds may just have reached breeding maturity and these beginners are eventually seen-off by their seniors, forming a subordinate group that exists at the periphery of the colony or become nomadic, taking no part in breeding. The counting of confirmed breeding pairs in a colony should not take place until this pre-breeding activity has been completed. |

Clearly the number of gulls that summer in this area exceeds the number that actually breed, fuelling the theory that the population in its entirety has the potential to expand considerably and rapidly. As previously stated, a considerable proportion of these non-breeding birds are of an age that is close to, or has reached breeding maturity. These birds are liable to expand existing colonies where space is available or seek out new sites amongst the abundance of unused suitable habitat.

Results at the completion of fieldwork end of August 2011.

Given that the regional breeding status of Herring Gull is currently regarded as uncommon, I have included probable breeding birds in these results.

Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus - all colonies remained stable over the four year study period resulting in an area total of 555 confirmed breeding pairs.

Herring Gull Larus argentatus - the number of confirmed breeding pairs remained stable over the four year study period resulting in an area total of 31 confirmed breeding pairs together with four probable breeding pairs.

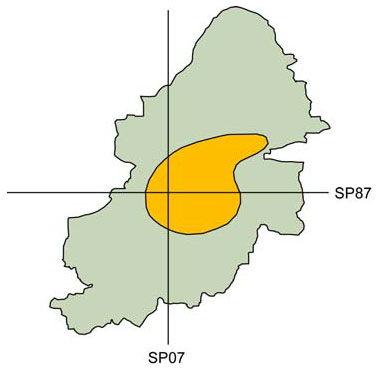

The adjacent map, figure 4 shows where the highest density of breeding gulls occur. This area spreads from the central zones in an easterly direction that follows the M6 - River Tame corridor. It is quite likely that this area, with its abundance of suitable but as yet unused breeding habitat, will continue to grow before birds colonise other areas. There are colonies that are detached from this core area but they are in an isolated position with regard to suitable habitat.

Figure 4. The nucleus of breeding birds

As with any survey of breeding birds the level of accuracy on which the final figures are based is subject to some tolerance. By focusing on placing a proof of breeding figure on the population of gulls that choose roof-top nest locations within this study area has allowed me to carry out the work without too much distraction from having to provide further statistics. The outcome of this is that I am comfortable with my final numbers, at the same time, I am perfectly happy in accepting that there will inevitably be a degree of inaccuracy in my findings. My reasoning for this acceptance is that not all nests are visible. It is impossible in many cases to gain a vantage point over roof-tops and in these instances my assessment of confirmed breeding is calculated entirely on the behaviour of adult birds and therefore subject to interpretation.

It is the intention that this work will provide a point of reference to any future study assessments concerning the roof-top nesting gull population that occurs within the Birmingham boundary. To this end I offer the following benchmark figures that incorporate an inaccuracy allowance of ± 10% of my findings. This figure of approximately 10% does not have any scientific value. My decision to use this percentage is based entirely on the lines that this survey area places before you a very difficult recording and monitoring environment for this particular study. Given these circumstances, it would seem reasonable to expect that somewhere in the order of 50 pairs, of the 555 recorded breeding pairs of Lesser Black-backed Gulls, may not fall correctly within this category level. That is to say, they should have been categorised as probable or possible breeding birds or simply present in the area non-breeding. On the other hand it would be equally reasonable to expect that the same figure of around 50 breeding pairs are likely to occur in the area but have not been recorded. Therefore, this figure of approximately 10% has been used simply as a gesture to accommodate any inaccuracies and in doing so provide final round-up figures with a high and low value.

Lesser Black-backed Gull chick, August 2009 and Lesser Black-backed Gull incubating eggs, May 2011. Central recording area. Jim Winsper

Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus - Final benchmark figures.

Figures at the completion of this study, end of August 2011, amount to a population not greater than 600 or less than 500 confirmed breeding pairs.

Herring Gull Larus argentatus - Final benchmark figures.

Any meaningful population increase or decrease that provides evidence of change to the 31 confirmed breeding pairs and four probable breeding pairs that exist at the completion of this study end of August 2011.

Tables 1 and 2 show the location of all colonies found in the area during the study period, the number of breeding pairs in each colony, a six figure OS grid reference and the British Trust for Ornithology tetrad code. Given that colonies have a tendency to relocate, albeit a minor move due to a variety of disturbance reasons or an expansion or reduction in numbers, the location together with the grid reference should enable us to locate the colony as it was at the time of study. The BTO tetrad code is the recording reference used for the location of species during the New Atlas fieldwork. It does, however, continue to provide a wider reference area in support of the other two procedures used in this study.

In the following two tables all locations are in BTO tetrad numerical and alphabetical order.

Table 1

|

Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus. All records 20082011inclusive |

||||

|

|

||||

|

Location |

Number |

OS |

BTO |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Longbridge works/Longbridge Lane |

09 |

SP009768 |

SP07 |

D |

|

Wiggin St/Rotten Park St |

07 |

SP048871 |

SP08 |

N |

|

Pitsford Street |

02 |

SP058879 |

SP08 |

N |

|

Ledsam Street |

03 |

SP052869 |

SP08 |

N |

|

Hockley Trading estate/Pitsford St.w. |

08 |

SP056880 |

SP08 |

P |

|

Charles Henry St/Vaughton St |

09 |

SP074856 |

SP08 |

S |

|

Lombard Street |

03 |

SP078859 |

SP08 |

S |

|

Barford Street |

02 |

SP074859 |

SP08 |

S |

|

Cliveland Street |

11 |

SP071877 |

SP08 |

T |

|

Summer Lane (middle) |

05 |

SP070879 |

SP08 |

T |

|

Constitution Hill |

02 |

SP065877 |

SP08 |

T |

|

Northwood Street |

02 |

SP062875 |

SP08 |

T |

|

Newhall Street |

03 |

SP065872 |

SP08 |

T |

|

Wholesale Market area |

05 |

SP075861 |

SP08 |

T |

|

Loveday Street/Price Street |

05 |

SP072877 |

SP08 |

T |

|

Colmore Row |

08 |

SP067869 |

SP08 |

T |

|

Council House-Victoria Square |

06 |

SP066869 |

SP08 |

T |

|

Cornwall St/Edmund St |

03 |

SP066870 |

SP08 |

T |

|

New Street west |

01 |

SP068868 |

SP08 |

T |

|

New Street central |

02 |

SP070868 |

SP08 |

T |

|

New Street east |

02 |

SP071867 |

SP08 |

T |

|

Corporation Street |

02 |

SP071868 |

SP08 |

T |

|

New Street Station |

01 |

SP069867 |

SP08 |

T |

|

Temple Row |

01 |

SP070869 |

SP08 |

T |

|

Wholesale Markets/main complex |

81 |

SP074862 |

SP08 |

T |

|

Rea Street |

02 |

SP076861 |

SP08 |

T |

|

Bull Ring Trading Estate |

02 |

SP079862 |

SP08 |

T |

|

Bishop Street |

04 |

SP073860 |

SP08 |

T |

|

New Town Row/New Town area |

11 |

SP064882 |

SP08 |

U |

|

Evelyn Road |

03 |

SP096838 |

SP08 |

W |

|

Armoury Road |

24 |

SP096849 |

SP08 |

X |

|

Sydenham Rd/Golden Hillock Rd |

14 |

SP095848 |

SP08 |

X |

|

Highgate Road |

04 |

SP086845 |

SP08 |

X |

|

Windsor Street |

06 |

SP080878 |

SP08 |

Y |

|

Fazeley Street |

05 |

SP080868 |

SP08 |

Y |

|

Barn Street |

04 |

SP080867 |

SP08 |

Y |

|

Upper Trinity Street |

05 |

SP083861 |

SP08 |

Y |

|

Dollman St/Inkerman St |

03 |

SP087874 |

SP08 |

Y |

|

Pennine Way |

26 |

SP095885 |

SP08 |

Z |

|

Rupert Street |

14 |

SP084884 |

SP08 |

Z |

|

Tame Road/Electric Avenue |

26 |

SP086902 |

SP09 |

V |

|

Seeleys Road |

09 |

SP100841 |

SP18 |

C |

|

Redfern Road Parkway |

11 |

SP114842 |

SP18 |

C |

|

Redfern Road/Kings Road |

03 |

SP110844 |

SP18 |

C |

|

Speedwell Road/Amington Road |

03 |

SP118847 |

SP18 |

C |

|

Warren Road |

07 |

SP105889 |

SP18 |

E |

|

Common Lane |

04 |

SP107888 |

SP18 |

E |

|

Watson Rd/Jarvis Rd |

115 |

SP100894 |

SP18 |

E |

|

Gravelly Hill |

38 |

SP101901 |

SP19 |

A |

|

Fort Parkway |

17 |

SP125901 |

SP19 |

F |

|

Fort Parkway east |

05 |

SP133908 |

SP19 |

F |

|

Erdington Industrial Park |

07 |

SP136914 |

SP19 |

F |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total confirmed breeding pairs |

555 |

|

|

|

Table 2

|

Herring Gull Larus argentatus. All records 20082011 inclusive |

||||

|

|

||||

|

Location |

Number |

OS |

BTO |

|

|

Colmore Row |

02 |

SP067869 |

SP08 |

T |

|

New Street east Probable B. |

01 |

SP071867 |

SP08 |

T |

|

Wholesale Markets/main complex |

02 |

SP074862 |

SP08 |

T |

|

Armoury Road |

05 |

SP096849 |

SP08 |

X |

|

Fazeley Street Probable B. |

01 |

SP080868 |

SP08 |

Y |

|

Rupert Street |

01 |

SP084884 |

SP08 |

Z |

|

Pennine Way |

01 |

SP095885 |

SP08 |

Z |

|

Watson Road/Jarvis Road |

16 |

SP100894 |

SP18 |

E |

|

Fort Parkway Probable B. |

02 |

SP125901 |

SP19 |

F |

|

Fort Parkway east |

02 |

SP133908 |

SP19 |

F |

|

Erdington Industrial Park |

02 |

SP136914 |

SP19 |

F |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total confirmed breeding pairs |

31 |

|

|

|

|

Probable breeding |

4 |

|

|

|

Herring Gull incubating eggs, June 2011. Recording zone 1. Jim Winsper

Herring Gulls that I have recorded as probable breeding birds refer to pairs that have summered in the area, in the immediate vicinity of active Lesser Black-backed Gull colonies. While all four pairs were involved in courtship behaviour, nothing more was revealed that offered absolute proof that breeding had actually taken place. However, it must be emphasized that viewing access to some of the roofs in these locations was severely restricted. It is also highly likely that the birds involved in these instances were first time breeders, lacking the necessary experience to complete their reproduction process. Breeding pairs of Herring Gulls form 5.3% of the total population of all recorded breeding gulls in this area and in the main choose to locate their nests in close proximity to, or within, Lesser Black-backed Gull colonies.

This species did not attain breeding status in this region until 1999 when a pair successfully raised three young in Worcester city, this being the first county and regional record. Following this, breeding success was confirmed in Birmingham city centre in 2001 when a pair raised three young. This record being the first for this location. (WMBC annual bird report)

Opportunism is a genetic trait that all bird species possess, on which their survival depends. It is characterised here by these two species of gull in its keenest form and especially so by Herring Gull, the archetypal seaside bird of the UK coast. During the 25 year period since breeding first took place in this region both birds have exploited what man has had to offer, a plentiful supply of food, through landfill sites in particular, safe roosting at the region's larger water bodies together with a wide range of building constructions that satisfy their breeding habitat requirements. Having been the providers we, mankind, are also in the position to deprive these birds of some of these facilities, none more so than their breeding habitat. Their presence as urban breeding birds is not always welcome and the conflict between man and bird is prevalent in many areas throughout this region, as it is in other parts of the UK where these gulls have colonised an urban environment. However stringent our preventative methods may be, these two species of gull will not be easily put off from going about their breeding activities in their chosen urban location.

What is the likely impact of this emergent population of breeding gulls in this area?

I would suggest that we look at this issue from two fronts. The first being, how will it affect us, the human population and second, the affect that this population might have on all other wildlife in the area? We can then add a third and combined component to these questions. What will be the effect in both instances if the gull population expands well beyond its present size? All of the usual problems associated with mass invasion by wildlife of public areas pop up again in this situation. The issues that are mostly linked to urban roof-top nesting gulls are noise, mess and aggression, prioritised in that order (Rock 2005).

Mess will certainly prove to be a problem. The city, having played host to winter Starling roosts containing many thousands of birds over an untold amount of decades, is testimony to this. However, the mess produced by nesting gulls goes further than just their excrement; their feeding habits and subsequent left-overs, together with frequent corpses of what is a large bird, plus their nesting material all generate a considerable amount of detritus. Nesting material itself is a problem, blocking roof-top waterway drain-off channels that can result in leaking roofs and internal flooding of buildings. In addition to this, these birds are naturally aggressive when it comes to protecting their nest site and defending their young. Those who enter their territory during these stages of their breeding cycle may well experience this trait.

Their presence in this area and the impact that this may have upon other urban wildlife does not, as yet, appear to have sounded any alarm bells. There are no other bird species competing directly with the gulls for their roof-top nest sites and their predatory instincts and activities appear to have a lot less impact on potential prey species than that of the resident corvid and raptor population. One bird species that may well suffer from the presence of breeding gulls is the urban dwelling Kestrel Falco tinnunculus. If the chosen nest site of the Kestrel happens to be favoured by the gulls as a suitable breeding location the Kestrel is soon ousted from its territory when gulls move in. This may not always be down to the action taken by the gulls and may well be a decision to move on by the Kestrel. The Peregrine Falcon Falco peregrinus is not affected by the presence of breeding gulls. Both species of gull and the Peregrine have a long association of breeding in close proximity to one another in coastal locations and their pact would also appear to apply in an urban environment too. Other noted species that may use the same building as the gulls to locate their nests are Feral Pigeon Columba livia, Common Starling Sturnus vulgaris and House Sparrow Passer domesticus, none of which are deterred by the presence of gulls.

While predation by urban gulls is of a fairly low level in this area at present, it must still be recognised as an additional threat to that already posed by other species and we should perhaps look at the whole picture rather than a fragmented version of species by species when evaluating the situation. Further to this, an increase in this breeding population of gulls, particularly on a large scale, could possibly see some changes in characteristic to their feeding behaviour within this environment and this is quite likely to involve a tendency toward a higher rate of predation in their food gathering methods. In particular, such changes may well apply in the case of Herring Gull, which of the two species is the bird with considerably greater predatory instincts. My only evidence of true predation by gulls throughout the four year study period is the taking of a Mallard Anas platyrhynchos duckling on the Birmingham & Fazeley Canal in Aston by a Lesser Black-backed Gull. It is quite likely that the duckling's seven siblings may well have suffered the same fate. As things stand it would seem that the gulls preferred feeding method is that of scavenging and while this source of food supply is plentiful then other methods of gathering food may well remain opportunistic and thus infrequent while the population remains at or around the current level.

What will happen next remains to be seen but the regional status of these gulls over the coming years is highly likely to take some twists and turns, be they self imposed or inflicted by man. One certainty is that this population will continue to fascinate and be worthy of future study.

Lesser Black-backed Gull incubating eggs on a warm day, June 2011. Recording zone 1. Jim Winsper

Acknowledgements

Many thanks go to Dr Stefan Bodnar for providing access to roof-tops in Birmingham city centre, Alan Dean for posting annual results of this survey on his website together with his support and constructive prompts on this article, Graham and Janet Harrison for their constructive comments, Alicia Normand for overhauling this paper, my wife Lilian for her invaluable assistance during fieldwork and the preparation of this article and finally to the West Midland Bird Club and the British Trust for Ornithology for their support and encouragement in my undertaking of this project.

References

Brown, A. and Grice, P. 2005. Birds in England. Poyser, London.

Cramp, S. 1971. Gulls nesting on buildings in Britain and Ireland. British Birds 64: 476-487.

Emley, D.W. A Checklist of the birds of Staffordshire, Warwickshire, Worcestershire and the West Midlands and Guide to Status and Record Submission. Third Edition 2011, West Midland Bird Club.

Emley, D.W. et al. West Midland Bird Club Annual Bird Report 1986 -2009. West Midland Bird Club.

Harrison, G. & Harrison, J. 2005. The new Birds of the West Midlands. West Midland Bird Club.

Mitchell, P.I., Newton, S.F., Ratcliffe, N. and Dunn, T.E. 2004. Seabird Populations of Britain and Ireland. Seabird 2000. Poyser, London

Monaghan, P.E. & Coulson, J.C. 1977. Status of large gulls nesting on buildings. Bird Study 24: 89-104.

Raven, S.J. & Coulson, J.C. 1997. The distribution and abundance of Larus gulls nesting on buildings in Britain and Ireland. Bird Study 44: 13-34.

Rock, P. 2005. Urban gulls. British Birds 98: 337-394

Republished from: Winsper, J. 2014. Roof-top nesting gull study: concerning the population of gulls that breed within the Birmingham boundary. West Midland Bird Report 78: 237-249.

|

|