Studies of an individual Yellow-legged Gull : a photographic essay

Studies of an individual Yellow-legged Gull : a photographic essay

|

Fig.1. Yellow-legged Gull in adult plumage (5cy), January 2012

Since the mid-1980s Yellow-legged Gull has become a regular visitor to the West Midlands region, with numbers now exceeding 100 individuals annually. There are records for all months of the year but with two distinct arrival periods: in late summer (peaking in July) and during mid –winter (peaking in November and December). The earlier peak reflects the annual post-breeding moult migration of Yellow-legged Gulls from southern Europe. The source of the gulls involved in the mid-winter peak is less clear but may involve wider geographical origins. The status of the species in the West Midlands region was described in detail in the West Midland Bird Club Annual Report No. 69 (Dean 2004) and is updated <here>.

Many observations of Yellow-legged Gulls (hereafter YLG) are from sites which attract large numbers of gulls, particularly landfill sites, roosts and favoured loafing areas. At such sites there may be a number of YLGs, some of similar age, which ‘come and go’ and which move between different sites. Although individual gulls may reside in the region for some time, it is rarely possible to identify and monitor a particular individual with certainty over an extended period. A rare exception to this has involved a YLG, then in second-winter plumage which arrived in the southern section of Kingsbury Water Park (KWP) in January 2010, thus just into its third calendar year. Remarkably, it remained for over 14 months before departing, presumably migrating back to southern Europe, but it has returned and resided at the site from July to January or late-December in each successive year to date (2025). Such prolonged presence has provided a singular opportunity to study a known individual. This article describes the results of these studies, based upon regular observations throughout the period of the gull’s presence. Issues examined include its developing phenology (seasonal ‘arrivals and departures’), moult and plumage development (from 3cy to adult), and behaviour (including interactions with other species and with a second YLG).

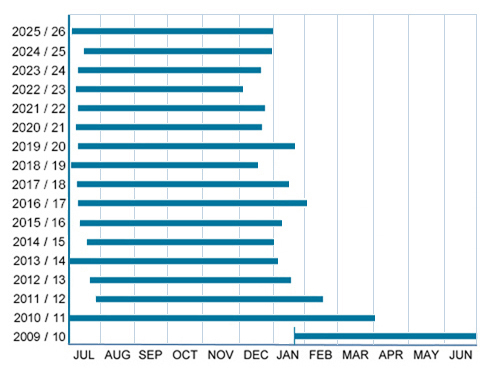

The YLG was first noted on January 20th 2010, during a brief respite from a prolonged cold spell, which began in mid-December 2009 and had brought heavy falls of snow and freezing of all but the largest and deepest water-bodies. The intense cold returned at the end of the month and persisted through February but the gull remained at the site, frequently standing on the ice. As spring approached, the expectation was that it would soon depart. However, the weeks –and then months – went by and it remained on site. In the event it remained until early April 2011, a remarkable 14 months and more since its arrival. Adding to the surprise, it returned to the site in July of that year and has done so in each successive year, generally arriving in early to mid-July and departing between late-December and early in the new year. The periods during which it was present between January2010 and December 2025 are portrayed in Figure 2 (plotted from summer through winter).

Fig. 2. Phenology of an individual Yellow-legged Gull at

Kingsbury Water Park, Warks, Jan 2010 to Dec 2025.

Since its reappearance in July 2011, its subsequent arrival dates have been consistently in early- to mid-July. However, the departure date was typically between early-January and early-February until 2020 but, since then, it has departed slightly earlier, before the turn of the year. This may reflect a tendency to return to its breeding area earlier, to re-occupy an established territory.

When it first appeared, in January 2010, the YLG was in its third calendar year and in what has traditionally been referred to as ‘second winter plumage’ (2W). It is a large and robust individual, presumed to be a male, a conclusion supported by the later attentions of a presumed female Yellow-legged Gull (see Behaviour).

Between late June and November 2010, it underwent a complete moult, in the process acquiring its 3W plumage calendar-wise. Interestingly, however, its appearance after this second complete moult was very much as would be associated traditionally with a 4W individual rather than 3W: very like adult apart from black in the primary coverts. The plumage traditionally associated with a 3W bird was effectively 'by-passed' (see Fig. 3g & 3h).

In subsequent years it progressed into fully adult plumage. The leg colour of the KWP individual showed evident yellow hues from 3cy. After attaining adult plumage, the leg colour on arrival in July up to 7cy was generally the rather duller yellow hue characteristic of adults in winter (Olsen & Larsson, 2004, Gulls of Europe, Asia and North America). Thereafter, it arrived with the full yellow hue retained from breeding plumage (see Figs. 21 to 23 and Figs. 25 to 27.). Limited head streaking was attained after the complete moult in some years up to 6cy but has not been apparent thereafter.

Figures 3 present images of the gull, illustrating its moult and plumage development from 3cy (2W) to 5cy (adult), between January 2010 and January 2012.

|

|

|

| 3cy, January 2010 (2W plumage) | 3cy, February 2010 (2W plumage) |

|

|

| 3cy, June 2010 (inner primaries dropped) | 3cy, July 2010 (2S plumage: head, neck & mantle

more adult-like but outer primaries, tertials and some coverts not yet replaced; bill with extensive yellow) |

|

|

| 3cy, August 2010 (at rest quite adult-like but

note all-dark primaries and dark marks in tertials |

3cy, August 2010 (outermost two primaries yet to be replaced) |

|

|

| 3cy, November 2010 (legs with weak yellow hue) | 3cy, November 2010 (primary moult complete). Appearance much as associated with 4W rather than 3W: quite like adult apart from black on primary coverts. |

|

|

| 4cy, March 2011 (bare parts now approaching adult appearance but legs paler than bill-base) |

4cy, April 2011 (note rich red orbital ring encircling eye) |

|

|

| 4cy, July 2011 (commencing third complete moult) |

4cy, July 2011 (outer primaries old, inner primaries dropped) |

|

|

|

4cy, October 2011 (inner primaries new, outer primaries dropped). Note slight head-streaking. |

4cy, November 2011 (like adult - though black mark persists on lower mandible ) |

|

|

| 4cy, November 2011 (primary moult nearly complete

: p10 just short of full length) |

4cy, December 2011 (primary pattern) |

|

|

| 5cy, January 2012 | 5cy, January 2012 (new primaries all fully grown) |

Fig. 3a to 3r. Plumage and moult progression from 2W to adult.

Selected portraits of the Yellow-legged Gull in adult plumage (between its seventh and eighteenth calendar years).

Fig. 4. Yellow-legged Gull, July 2014, newly

arrived for its fifth session at the site and now in its seventh

calendar year.

This is the first time that the gull arrived with black lacking

entirely towards the tip of the bill.

Fig. 5. Yellow-legged Gull, July 2016, now in its ninth calendar year.

Fig. 6. Yellow-legged Gull, July 2017, now in its tenth calendar year.

Legs more richly yellow than at any time hitherto. Bill and gape also very

colourful. Effectively appearance still that of breeding season.

While 'gaping', it can be seen that red gonys spot extends just onto upper

mandible.

Fig. 7. This image was taken on January 20th, 2020, ten years to the day

since the Yellow-legged Gull first appeared at KWP.

It was then in 2W plumage and in its 3cy. Here it is entering its 13th cy.

Fig. 8. Yellow-legged Gull, July 2023, now in its sixteenth calendar year.

Fig. 9. Yellow-legged Gull, July 2024, in its seventeenth calendar year.

Fig. 10. Yellow-legged Gull, July 2025, in its eighteenth

calendar year

(and its sixteenth 'session' and seventeenth

winter at the site, the first session having embraced 14 months and parts of two winters).

The YLG is very much a loner and spends the greater part of most days around the lake, where it loafs, feeds and even roosts alone. Very occasionally it is absent for an entire day but, typically, it is present throughout the day or disappears for no more than an hour. Most inland-wintering gulls gather in large assemblies at or close to feeding sites such as refuse tips or at nearby loafing sites through the daylight hours, before moving in the late afternoon to form even larger gatherings at roost sites at reservoirs, lakes and gravel-pits. YLGs certainly join feeding assemblies of large gulls at refuse tips and join traditional overnight roosts but rather solitary daytime behaviour of at least some YLGs, at least during daylight hours, has been noted before, for example by R. A. Hume as long ago as the mid-1970s, when observing michahellis at Chasewater, in Staffs, (though at that time the true identity of these 'yellow-legged gulls' with dark mantle and very white head in mid-winter was not yet established) British Birds (1978) 71: 338-345.

During the periods it has been under observation, the Kingsbury bird has spent 80% of its time simply ‘loafing’. It favours a particular ‘yachting pontoon’, where it rests down on its haunches and frequently sleeps with its bill and forehead tucked under its scapulars (Figure 11). In warm weather it sometimes holds its bill open, apparently using 'panting' as a cooling technique (Figure 12; July 2013, 24oC).

|

|

|

|

Fig. 11 |

Fig.12 |

A second favoured resting (and observation) point is at the top of the yachting centre’s flag-pole on one of the islands (Figures 13).

|

|

| Fig. 13a | Fig. 13b |

More adventurous observation points include the very top of one of the electricity pylons (transmission towers) which cross the site and which are some 40 metres high (Figures 14).

|

|

| Fig. 14a | Fig. 14b |

It has also perched on the top of a flag-pole positioned on the apex of the tower at nearby Kingsbury church (Figures 15).

|

|

|

Fig. 15a |

|

|

|

Fig. 15b. Zoomed detail from Fig. 15a. |

Very occasionally, the YLG has been absent for an entire day, though on one such day it was observed to return at dusk and, as suggested by other late afternoon observations, it appeared to roost on-site. Sometimes its 'away-days' coincide with considerable water-borne yachting activity (and associated disturbance) but at other times there has been no obvious local reason. It is assumed that these sporadic absences involve feeding expeditions elsewhere. Feeding activities on site are observed regularly but appear to occur only once or twice on any given day (see below). Even allowing that its occasional absences involve feeding expeditions, it is clear that the gull is able to meet its food requirements in a relatively short space of time and is able to spend a proportionately large percentage of its time simply ‘loafing’.

Preening

As well as resting, bouts of preening are regular, sometimes lasting up to 40 minutes at a time. The images below (Figures 16) record a preening session on August 26th 2013, when the primary moult was in progress. Despite the fact that the outermost primaries were about to be replaced, they still received considerable attention. The ability of the gull to manipulate its wings, head and neck during preening is well-captured in this sequence of pictures.

|

| Breast and underwing coverts receive first attention |

|

| Note five new inner primaries, with black

subterminal band on p5. P6 to p8 have been dropped while p9 and p10 are old. |

|

|

| Tail, undertail coverts and flanks receive attention |

|

|

|

|

| Finally, the flight feathers |

|

| With preening session complete, the gull gave the 'long call' |

Fig. 16a to 16i

Feeding activities

As noted above, the YLG spends such a high proportion of its time simply loafing and, clearly, it is able to meet its feeding requirements in a relatively short period of time. During its first year of residence, it would sometimes fly in towards the shore when human visitors to the park were feeding other birds, creating a visible feeding assembly of geese, ducks and Black-headed Gulls, but later it has shown little interest in these activities. On September 30th, 2013, it was observed feeding in a stubble field adjacent to the water-park (Figures 17). There were Black-headed Gulls present but no other large gulls.

|

|

|

| Fig. 17a | Fig. 17b |

Otherwise, its observed feeding activities have generally involved capturing or scavenging fish from the centre of the lake (see Fig. 18a, showing the gull as a 3cy capturing a fish in mid-water, and Fig. 18b, showing a zoomed image of the fish in the gull's bill).

|

|

|

Figs. 18a and 18b.

On February 13th, 2012, a fish was stolen from a Cormorant at the moment the latter surfaced. The fish are invariably of some size. The YLG will generally peck at the fish in mid-water, tearing off strips of flesh and such activity will continue for up to 30 minutes. On some occasions, fish are dragged to the shore (or onto the ice when the lake has been largely frozen), from distances of up to 200 metres across the water and taking some considerable time and effort to achieve. The images below (Figures 19) record one of these occasions, involving a 30 cm Bream, on April 1st 2011.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The Bream was initially some 200

metres from the shore. The gull was able to drag it only a few metres at a time and it took about 5 minutes for it to reach the shore. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A presumed female LBB (based on size)

joined the meal and was tolerated. Generally, any competitor species is treated aggressively. |

|

|

|

| Meal complete. |

Given opportunity to feed 'selectively' on land, the innards of the fish were preferred (see 11j) and scaled skin left largely intact. However, on other occasions, an entire fish would be swallowed (see below). |

Fig.19a to 19n.

On a second occasion, December 12th 2012, the extent to which large objects can be swallowed by gulls was well-illustrated, with the neck of the gull becoming very conspicuously distended (Figures 20).

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figures 20a to 20f

In August 2025 the gull was observed apparently feeding on a heap of waterweed (plate 21), though perhaps aquatic insects and snails secreted therein were the target.

|

|

Fig. 21.Yellow-legged Gull apparently feeding on weed, August 2025.

Interactions with other species

In Fig. 19k & 19l, note that a Lesser Black-backed Gull (perhaps a female on size) was allowed to feed on the fish which the YLG had dragged to the shore. Perhaps the same LBBG was observed in close attendance with the YLG on several other occasions up to its fifth calendar year (see below). This toleration was very much the exception however. Typically the gull is decidedly solitary, residing alone on its favoured pontoon (many plates in this text show it loafing, feeding or preening on this structure). A few Black-headed Gulls are generally tolerated if not too close (see below for a dramatic exception in November 2025) but larger gulls invariably receive an aggressive response.

When the YLG is feeding away from the pontoon, intruders also initiate an aggressive response, involving posture and calls. The series of images below (Figures 22) show the interactions of the YLG with Crows and a Herring Gull on February 13th 2012, a cold spell when the lake was largely frozen.

|

|

| Initially feeding undisturbed | As Crows approach, YLG adopts the 'Aggressive Upright-posture' (cf. Fig B in BWP3 Herring Gull account). |

|

|

| Adopts 'Long Call and Throw-back' posture (see Fig. E in BWP3 HG account) |

Crows remain and are joined by a 2W-type Herring Gull. YLG responds by shrouding fish with arched wings. |

|

|

| With Crows persisting in their attentions, the YLG lifts the entire fish and swallows it whole. | |

|

|

|

With just tip of the fish's tail protruding from bill, note how the neck and breast of the YLG are visibly distended. |

Still looking distended, the YLG appears somewhat uncomfortable. Shortly afterwards it went to water's edge and took a drink. |

Figures 22a to 22h

Figure 23 shows the gull on the shoreline adopting the 'Aggressive Upright Posture' (Tinbergen 1953, Cramp, S & Simmons, K.E. (eds.) 1983), which was directed at a nearby Lesser Black-backed Gull.

|

Fig. 23. Yellow-legged Gull adopting 'Aggressive Upright Posture', August 2024.

On a few occasions during the first two-and-a-half years (but not thereafter), the YLG did interact with (and tolerate) one or more presumed female Lesser Black-backed Gulls (Figures 19k & 19l and Figures 24). Generally, however, it has rarely tolerated close attendance by any potential competitor.

|

|

|

|

May 31st 2010 |

August 1st 2012 |

Fig. 24a & 24b. Yellow-legged Gull with Lesser Black-backed Gull(s)

Interactions with another Yellow-legged Gull

In late-June and early-July 2013 (before the (now) adult had returned), a 4cy Yellow-legged Gull appeared at the site and likewise spent most of the daylight hours around the lake, even perching on the same pontoon and flag-pole as used by the adult individual (Figures 25).

|

|

|

|

A second Yellow-legged Gull, a 4cy individual, appeared in June & July 2013 and used some of the same resting/perching locations as the (now) adult, which had not yet returned to the site |

|

Fig. 25a & 25b

This individual departed in mid-July, just days before the (now) adult returned to the site. However, what was judged to be the same 4cy reappeared in mid-October. It was a smaller individual than the long-term adult and perhaps a female. It showed interest in the adult but was vigorously chased away, such that it at times resorted to an adjoining lake (Hemlingford Water). On November 1st 2013 it flew to land on the water close to the adult, which responded by adopting a presumed aggressive posture and the 'intruder' retreated (Figures 26).

|

|

|

|

Fig. 26a & 26b. Interaction of two Yellow-legged Gulls: 4cy on left and long-staying adult on right |

Undeterred, the 4cy later rejoined the adult when it was loafing on its favoured pontoon (Figure 27). The adult initially ignored it but then stood up and chased off the 'intruder'.

|

|

|

Fig. 27. 4cy YLG on left and long-staying adult on right |

A sustained attack on a Black-headed Gull

Other LWHGs which occasionally attempt to land on the YLG's favoured pontoon are habitually treated aggressively and quickly displaced. Traditionally, however, Black-headed Gulls - which frequently loaf on this pontoon - have been tolerated and ignored. During 2010 to 2024, I witnessed no aggressive responses from the YLG directed at BHGs, which suggested that the YLG did not regard BHGs as competitors. This tolerance all changed in dramatic fashion on November 17th, 2025. About 20 BHGs were loafing on the pontoon, while the YLG was at that time resting on the water some distance away. Then it flew in and landed on the pontoon. Within moments, it began a sustained attack on an adult BHG, which already had a damaged left leg (dangling from the underbody and with the webbing of the foot collapsed ('club-foot' like), as is not infrequently seen in gulls). The YLG grabbed the BHG by the very base of this leg and wrestled its victim to the floor of the pontoon. For several minutes it pulled the BHG to-and-fro and, despite its vigorous struggles, the BHG was manipulated into various contorted postures, as the YLG pulled its leg into all sorts of unnatural angles. The wings of the BHG became dishevelled as it struggled to break free. Just as it looked as though the BHG must succumb, the YLG released its grip on the leg and the BHG attempted to fly off. As it did so, the YLG grabbed at its right wing and the two gulls tumbled into the water. Unexpectedly, the YLG did not then pursue it's attack but flew back up onto the pontoon. After lying in a rather crumpled fashion in the water, the BHG recovered sufficiently to make its escape and fly away. The motivation for the YLG's prolonged attack appears obscure, particularly its focus on the extreme base of the damaged leg of the BHG. There is relatively little food value in a gull's leg and the YLG may have hoped to subdue the BHG to a point where it could release its hold on the leg and turn its attention to the body. However, this would not explain the targeting of the very base of the tibia. It would have been much easier to grasp the tarsus and relatively difficult to grasp the very base of the tibia where it joined the body. The YLG gave every impression that it was attempting to 'amputate' the BHG's leg at the base. Injured birds will often be targeted by predators but gulls with a damaged leg are quite frequent and there have regularly been BHGs with a damaged leg among assemblies on the YLG's favoured pontoon Yet this was the first instance in over 15 years that I have witnessed it launch such an attack. The photos below show the episode in detail.

Fig. 28. The YLG commences its attack, grabbing the BHG at the base of the tibia and lifting the leg above the tail.

Fig. 29. The BHG is wrestled onto the floor of the pontoon. The YLG

has the very base of the BHG's leg in its grasp,

with the remainder of the leg displaced through the gull's underwing

feathers

Fig. 30. In clear distress, the BHG is then lifted clear of the pontoon, with its wings displaced.

Fig. 31. Still grasping the leg, the YLG thrusts the BHG back onto the surface of the pontoon.

Fig. 32. Twisting its own head and neck, the YLG continues to

manipulate the base of the BHG's leg

(here the leg can be seen in a completely unnatural position, rising

vertically along the side of the YLG's head).

Fig. 33. The BHG still manages to get up onto its 'good' leg but

cannot escape the grip of the YLG.

Note the dishevelment of the BHG's right wing.

Fig. 34. The BHG is once more wrestled to the floor, with the YLG still grasping the base of its left leg and the BHG's head, neck and wing contorted.

Fig. 35. The YLG eventually releases the leg of the BHG, which

attempts to fly away - but the YLG grabs at the edge of its right wing.

Immediately after this, both gulls tumbled into the water and the YLG

released its grip.

Fig. 36. The YLG did not renew its attack but flew back up onto the

pontoon, where its demeanour showed no indication of the preceding

events.

After resting in a rather crumpled position in the water, the BHG

recovered sufficiently to fly away.

|

|

|

|

Home |

Mediterranean

| Laughing |

Franklin's |

Little |

Sabine's |

Bonaparte's |

Black-headed |

Ring-billed | Common |

Lesser Black-backed | |